INTRODUCTION

In 1899, The Szeged Jewish Community announced a design competition for the construction of a new synagogue. The Jewish Community of Subotica, which in the meanwhile strengthened in its social significance and population, already owned a site at the corner of Széchenyi square and Jókai Street, which was donated by Adolf Geiger on April 19, 1892.1 Intending to build a synagogue, the directorate of the Subotica religious community under the presidency of Dr. Izidor Milkó followed the Szeged competition with huge attention. Lipót Baumhorn (Kisbér, 1860 – Kisbér, 1932), the great synagogue-designer, won the first prize, with a traditional, „free style” design. Marcell Komor (1868, Pest – 1944, Sopronkeresztúr) and Dezső Jakab (1864, Biharréve – 1932, Budapest), partner architects from Budapest applied with an unusual shaped, „new lined” synagogue design, but despite being supported by Ödön Lechner, a member of the jury - the architect who invented the „new Hungarian national style” - their designs did not win the likes of conservative taste evaluation committee. Nevertheless, the jury recommended their design for purchase together with several other tender designs.2 The Subotica Jewish Community, which was already beyond an unsuccessful synagogue design contest, immediately took over their design drawings. The construction company of Ferenc Nagy and Lukács Kladek won the competition for execution with 197,818 crowns and 43 filler cost estimates. There were still missing 60,000 Crowns (40%) of the real cost of the construction.3 The majority of the necessary initial capital was provided by the members of the community by pre-emptying the seats: „The attached purchase conditions are fair and even the most financially modest community member can buy a seat because the purchase price will be paid in only 20% installments over five years.”

The amount needed to complete the construction was also secured by bonds with a 5% interest rate, which was the idea of the president of the community Izidor Milkó. After the designs were with minor changes adapted to the local conditions, in 1900 the construction of the new Subotica synagogue began. In the meantime, the designers have easily succeeded in convincing the management of the community to build the new synagogue in a „Lechnerian oriental / Hungarian style”. The building was completed by on-site supervision of Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab in about three years. The structure was already finished in the autumn of 1902, but the additional works took another year. The consecration of the synagogue was held on September 17, 1903, which the contemporary press reported as follows: „In Subotica, on September 17, the extraordinary, new temple of the Jewish community was put into use. The sacred feeling of fraternity, which increased the whole feast, was much more fascinating than the solemnity and magnificence of the temple itself, and the day was not made simply as a day of a temple consecration, not as a feast of a solemn confession, but as a holiday for the whole Subotica population.

Started with the sheriff - the representative of the state - to the plain citizen, for a few hours, Subotica’s whole life focused around the new synagogue. Along the altar the leaders of the official and religious life of

Subotica gathered: the authorities, the state officials, the military representatives and the priests of all regions. Outdoors, around the temple, the army of not invited citizens standed still in order, without any extrusion. In the afternoon, though the sky was darkened, it was a very nice weather for the holiday, about which the next report tells: After the singing of the evening prayer, Mór Kuttna chief Rabbi in a brief touching speech said good bye to the old temple, then they took out the Torahs from the Ark, and the local and guest priests along with the oldest members of the Jewish community took them to their arms and started to walk under two tents toward the new church. The tents were surrounded by ordinance officers in parade uniforms with extracted swords proceeding; in front of them the fire brigade played old Jewish prayers, followed by a large crowd behind. It was about four o’clock when the crowd arrived to the new temple’s square, where already thousands of spectators were waiting. In front of the locked gate of the temple, the mayor of the city, the officials in charge, and the leaders of the Jewish Community stood, and when the Torahs arrived in front of the stairs, Dezső Jakab architect, who with Marcell Komor, together designed the great temple, addressed a speech to the president of the community, and handed over the gilded temple key which rested on a velvet pillow. The president, Dr. Géza Blau, when taking over the key asked the mayor Dr. Károly Bíró, in a lively speech to take over from him and hand over the temple to his sacred purpose. Károly Bíró responded in a longer speech, opened the gates of the temple, and appealed for it, to serve as a shelter of good moral. Huge ovations of joy roared through the wide street, and the procession started into the church already completely full of audience. While the people were moving inside, psalms were sung by the temple chorus. After singing the psalms, the Torahs were put in front of the Ark, while the choir chanted the prayer starting „How beautiful are your tents, Jacob…” Then they placed the Torahs into the Ark. Lifschitz, the main chanter intoned the usual Saturday prayer in his sonorous nice voice, and along with Kuttna and Singer chief-Rabies carried the Torahs remained in their arms around the altar and placed them into the Ark. Then the greyhead Mór Kuttna blessed. He first blessed the church and then the audience. Then he raised the Eternal Flame. At that moment, all the electric lamps were lit at the same time, and illuminated the beautiful temple. At this reverent scene, a beautiful old Jewish prayer was heard by Gina Szőgyi the wife of Dr. Mátyás Klein, accompanied by the beautiful music of the organ. On the last chords of the song, Dr. Bernát Singer, came up to make his great speech, his beautiful festive speech, which he introduced with a great prayer. The deeply profound speech was followed by the Hymn. After the end of his speech the audience left and the believers said the evening prayer.”5 The quote may be particularly interesting in the present when the internal and external renovation of the building is completed. It evokes the process and mood of the day and the „initiation ceremony” when, at the same time the turn of the 20th century guidelines of the architectural development and urban-genesis of Subotica was born. On that day, in the sometimes dusty, otherwise muddy borough, the miracle-box opened, and the next fifteen years of urban development led to the fact that Subotica could rightly be called the city of Art Nouveau. The Subotica synagogue has become one of the most beautiful and most specific ones in East-Central Europe.

THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE CONSTRUCTION

While most of the synagogues in East-Central Europe were built in the second half of the 19th century in a dominant style of historicism or in a „Moorish style”, the Subotica temple - since it was built relatively later - carries the stylistic features of the „Hungarian Style of Art Nouveau”, thus it is a unique example in the region. The self-conscious Subotica Jewish Society chose this style, because at the turn of the century their assimilation efforts evolved. Through the course of the history, the economic strength and the current social and legal status of the Israelite community allowed for the first time their new sanctuary’s Byzantine dome to rise above the city’s silhouette equally along with the other temples of the town (Franciscan Church, Catholic Church of St. Teresa of Avila, Serbian Orthodox Church, etc.) influencing, shaping the city landscape and anticipating the directions of the future architectural development of Subotica. This trend was not a unique phenomenon for the city, but became a common feature throughout the Monarchy. In 1925, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the existence of the synagogue, the Subotica Jewish Community published a special edition of the „Szombat”, in which Izidor Milkó, the contemporary community president and writer, wrote about the circumstances of the construction: „We did not have much money. Already at the time of the Emeritus, enthusiastic President of our community, Mór Kunetz, in the nineties of the last century, the movement started to create a church-building fund. In the form of interest rate loans, it was possible to bring together some amount of money, but it was far from being the base for a larger proportion of construction – at least it could have been the starting point for it. The excellent developed plan of Ignác Kunetz which provided a substantial part of the construction capital by the sale of the temple seats brought forward the stage of implementation.

But we still did not have enough money to start bravely the great work and to look forward calmly and surely for the pay-off. At that point the idea came to me to release bonds with a 5% interest rate, which would be redeemed from the kind-hearted creditors little-by-little. (...) At that time - unbelievable but still true - I was very popular, moreover I was at the top of my popularity, and in three or four days I placed almost thousand of fifty-crown bonds. This success gave a new enthusiasm to the construction. I have a pleasant memory about this campaign, that the bonds have been noted without distinction, and even those have bought them with confidence who, with or without reasons were known as anti-Semites. In Subotica there had never been real anti-Semitism, and the religious denominations as well as the nationalities lived in exemplary peaceful coexistence and entente cordiale with each other...“ memory about this campaign, that the bonds have been noted without distinction, and even those have bought them with confidence who, with or without reasons were known as anti-Semites. In Subotica there had never been real anti-Semitism, and the religious denominations as well as the nationalities lived in exemplary peaceful coexistence and entente cordiale with each other...“

Because of the limited finances, it was necessary to make compromises during the construction of the synagogue. Poorer quality and low cost materials were used: instead of majolica, terracotta and gypsum decorations were placed on the façades; the footage was built from artificial stone instead of Siklós red marble; the surface of the Torah Ark and the Bimah was made of artificial marble (stucco); instead of gold plating, bronze was used, and the organ was also a modest size - with decorative false wooden pipes. This fact has greatly contributed to the rapid deterioration of the condition of the building and has also caused many dilemmas and difficulties during the renovation.

The cost of construction of the Szeged synagogue exceeded five times the cost of the Subotica temple (760,000 Crowns), yet: „Fortunately, the architectural effect and artistic value - obviously - is not linear in terms of financial expense. Moreover, financial constraints could benefit certain buildings. In terms of material richness and abundance, the Szeged synagogue is far superior to the Subotica temple, but the latter with its shape, relative simplicity and purity represents uniqueness.” Since the synagogue proved to be a successful project, as a result, the Municipality of Subotica ordered the designs of the New City Hall from the same architects. It was built in the period of 1908-1912, and by the present times, it has become an internationally renowned masterpiece of late Hungarian Art Nouveau. Between 1923 and 1925, after a heavy storm, considerable renovation and some alterations were carried out on the synagogue, but these did not modify significantly the essential appearance of the building. At that time, most of the stained glass windows of Miksa Róth (1865, Pest-1944, Budapest), the Imperial and Royal court glass artist of the time, were replaced and only a few were left from the original Tiffany stained glass pieces. On that occasion the external wall surfaces were stripped and re-plastered but without the decorative profiling and original colors. It is a big question whether the glazed majolica capitals from the top of the semi-circle pillars of the central dome disappeared that time. The original coloring above the chorus gallery was over-painted and changed. The repair of the windows was made by János Szanka (1879-1927), a stained glass painter from Szeged, who moved to Subotica in 1905.

ARCHITECTURE, STRUCTURE, ARTS

The building is standing on a large corner-site between the Synagogue Square and the Square of Jakab and Komor, and is, according to the dominant practice, detached, built withdrawn from the street regulation lines. There were three other ground-floor buildings standing on the plot: two smaller ones, the kosher butcher’s house and the home of the caretaker (behind it there is the gym of the former Jewish school), and the considerably larger building of the Jewish school, which was, as a result of an unsuccessful plot-speculation, demolished in the 1980s. The one-story building of the Jewish Community is standing on the plot oriented to the former Battyányi, today Dimitrije Tucović Street. It is still in use as a prayer hall, where the faithful Jews of Subotica have gathered to the present, and is also used as community facilities. The community building, the former school, and the kosher butcher’s house were also designed by Jakab and Komor. The remained buildings now form a protected architectural unity with the synagogue.

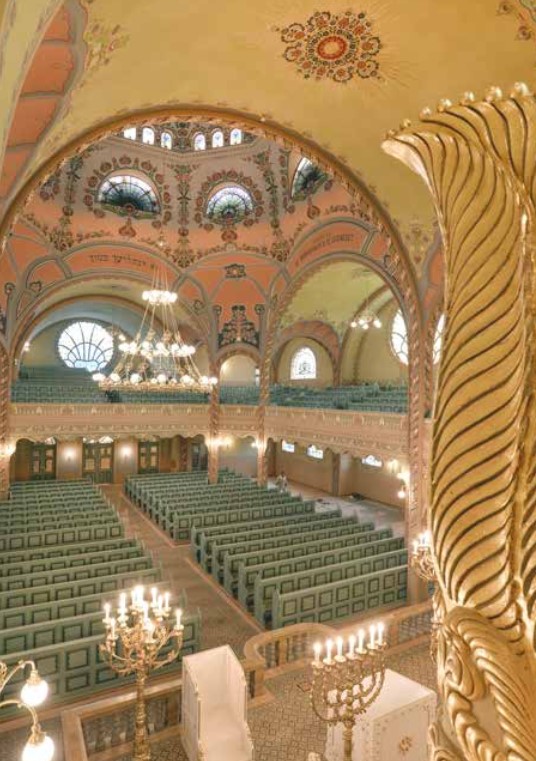

According to the typology of Rudolf Klein, PhD, the Synagogue of Subotica belongs to the Byzantine church type synagogues. Actually, it is crowned by a large Byzantine central dome, accompanied by four smaller corner cupolas (clock-towers) covered by colored glazed flat-tiles. The temple has a regular, 25 x 25 meter square shaped central prayer space, and an orthodox cross-reminiscent floor plan, similar to Christian churches. Four pairs of symmetrically ordered steel stanchions carry the entire structure of the prayer space, with the galleries and the central rabitz shell-structure cupola enforced by counter-ribs from the upper side. The height of the interior is 25 meters and the inner dome is 12.6 meters in diameter. There were 950 seats for the men on the ground floor, and 530 seats for the women on the three-side gallery. Four gates, entries and staircases on the corners provide access to the galleries, while, besides the west side main entrance, there are direct entrances to the ground floor on the south and north sides as well.

„The square plan follows the Ashkenazi orthodox tradition, the rabitz dome, as emphasized by architects, is reminiscent of the tents in the wilderness. Actually, the latter was much simpler than its incarnations in modern times.”

Since the Synagogue was used by reform Jews, the Bimah is not in the center but on the east side. „The synagogue in Subotica follows precisely this pattern of reform synagogues highlighted not only in its architectural expression, but also by the term ‘templompalota’ (temple-palace) spelled out by its architect, Dezső Jakab. However, its intellectual background is more complex and contradictory.”9 This is also apparent from the fact that architects used a multi-layered symbolism when formulating the details of the exterior and the interior. On the building, universal archetypes, Jewish religious iconography, vernacular symbolism, and Freemason symbols are combined through the organic interrelation of the universal „the Whole” and the unique „the Detail”.

About Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab, Réka Várallyay wrote: „In addition to their common artistic commitment, it is worth to mention that both of them belonged to the Freemason Lodge „Galilei”. Komor Marcell’s Freemason membership was advantageous for them in getting several commissions; for example as in Subotica, where Mayor Bíró Károly, or in Marosvásárhely where Mayor György Bernády belonged to the ‘brotherhood’.”

Taking a walk around the building, the visitor will notice that the synagogue is crowned by the central dome, with the Star of David on the top, symbolizing the unity of the heaven and earth. On the top of the corner domes above the clock-towers there are also placed Stars of David, which - according to the contemporary descriptions - were originally gold-plated. Corner domes symbolize the four Cardinal directions of the world and the passage of time. The dome as such, usually signifies the heaven, the spiritual sphere, and the square/rectangular building below it, symbolizes the earth and the material world. Between the two elements, stands the octagonal dome drum, which realizes the transition, referring to the harmony and assonance of the Universe. The symbolism which recalls the archetype of the Universe also appears in the external and internal horizontal division of the synagogue. The façades can be divided into three horizontal zones. The bottom zone, the closest to the ground, includes a pink artificial stone made socket and a wall-strip covered by red façade bricks, symbolizing the material world, the earthly form of life. The zone above is worked out with alternating red façade brick and plastered surfaces, which were originally decorated by terracotta elements with relief floral motifs, and arched or round shaped stained windows. This zone is enclosed from upside by a billowy merlon also decorated with reliefs of floral motifs. This intermediate zone is representing the earthly paradise, the lost Garden of the Eden. It is a transition between the material and the heavenly, spiritual world, which is represented by the highest zone - the world of the domes. The domes were originally covered with masterpieces of ornate, zinc-plates. In the seventies and eighties of the last century, hoping for longer durability they were replaced by copper plates. This has substantially altered the appearance of the synagogue. The external beauty of the synagogue is emphasized by the interchanging of

the plastered wall surfaces, and the ones covered by red façade bricks, as well as the artistic variety of brickwork appearing on the façade walls. The face work is enriched with the decorative embossed terracotta elements made by the world famous Zsolnay Porcelánmanufaktúra Zrt. in Pécs, which, due to their poor condition, during the restoration were entirely replaced with engobed pyrogranit. Every detail of the building shows the high-quality craftsmanship carried out by Ferenc Nagy and Lukács Kladek, construction contractors from Subotica, and their subcontractors, as well as the implementation of the all-in-one conscious planning characteristic for the era.

The main entrance of the synagogue can be approached from the west side. The visitor finds himself on the stairs in the front of three gates. In the middle there is the main gate, its dimensions are even more emphasized than the other two. The arched openings above the gates are decorated with colorful stained glasses. The carpentry and the wrought iron items are shaped in the „Lechnerian” style of the Art Nouveau. The arched reveals were originally covered by relief terracotta with a series of tulip motifs growing out of heart shaped figures. During their restoration, these were also replaced with engobed pyrogranit. „The nartex has three jambed entrances decorated with Hungarian ceramics, topped by wavy Matyó embroidery with poppies, conveying the message that everyday troubles should be left behind when entering a synagogue.”11 On the gable above the rosette there are three oculus, with Stars of David inside.

These round openings originally provided the ventilation of the loft. On the top of the gable stands one of the four Tablets of the Law. During the restoration, these were also newly produced in Pécs from glazed pyrogranit. On both sides of the nartex stands a brick corner pillar, which summons the column of Jachin (for the repentants) and Boaz (for the revelers) that originally stood in front of the Temple of Solomon. These may also be Freemason symbols, but they also fully correspond to the iconography of the Jewish synagogue architecture. According to the descriptions of the contemporary newspapers, originally on the top of these pillars were poppy-shaped majolica capitals - now only their terrazzo copies are visible. Similar capitals were on the top of the eight round corner-pillars placed around the central dome. These have disappeared mysteriously over the years, and were only rebuilt and replaced by the author of this booklet during the roofworks in the 2004-2011 period, restoring that way the original splendor of the main dome.

Through the gate, the visitor arrives to the vestibule and then to the men’s foyer. In the vestibule from the left stands a different style ritual handwash, carved out of pink stone, which was saved from the old demolished synagogue. The foyer has no natural illumination, so the artificial light creates a mystical twilight, as it prepares the visitor for the soul-lifting experience of the holy place under the central dome. There are memorial

plates on the walls. On the north wall from the left side, stand two white marble tablets where in Hungarian and Hebrew, the names of the deceased members of the Subotica Jewish Community are visible, along with the names of its founders. On the east wall, left from the central entrance there is a white marble plate with the worship timetable and to the right stands a memorial plate in honor of Mrs. Gitl who donated donations boxes to the synagogue in 1922. The Art Nouveau style plate on the south wall was set to Adolf Geiger, the most important donator, and the other to János Halbrohr and his wife, born to Netti Spitzer, one of the founders. As he crosses the doorstep of the holy place, the visitor will first notice the bench-rows, and then catch the site of the Torah Ark (Aron HaKodesh), but the central dome still remains hidden by the low ceiling – the bottom of the gallery. On the both sides of the entrance doors, deepened into the walls Art Nouveau shape, metal donations boxes can be seen. The miracle for the visitor opens only after a few steps, when the soul-inspiring sight of the huge celestial foliage-tent-like dome shows up. There is no one in whose soul then the flame of devotion would not light up...

You can also find the symbolism of the exterior of the building in the interior of the temple. Here is the inner breath-taking central dome, the ‘Tabernacle’, materialized as a shell structure, which, according to its designers, is intended to recall Moses’ Tent of Gathering. The central dome rises above the square floor plan of the holy place, supported by eight steel columns placed in octagonal order. Women’s galleries are covered with thin-shell arches, and shallow cupolas in their corners.

The ground plan kept the three-part spatial division (Foyer, Holy-place, and Inner Sanctuary – the Ark) of the Temple of Jerusalem, without the court, but at the main-gates and at the corner women’s entrances, the designers planned porches/windshields. The ground plan of the corner narthexes is quarter circular, and they are covered with artistic worked copper-sheet. The inner space, just like the exterior of the temple, is vertically divided in three parts. Here, too, there is the zone symbolizing the materialistic world, the earthly existence – that is the holy space under the galleries, where the bench rows of the faithful men are standing. Here is the Bimah - where the Torah is read from, and from which the Torah Ark opens. On the Bimah stand two Menorahs and two Hanukias with nine candle-holders, which is a practice to light in Hanukkah during the festival of light. From this space, the slander steel columns, which hold the galleries and the central dome, are set off and raised up. Their stucco coating is on one hand fireproof, and on other, their floral relief decoration is a part of the iconography of the Garden of Eden.

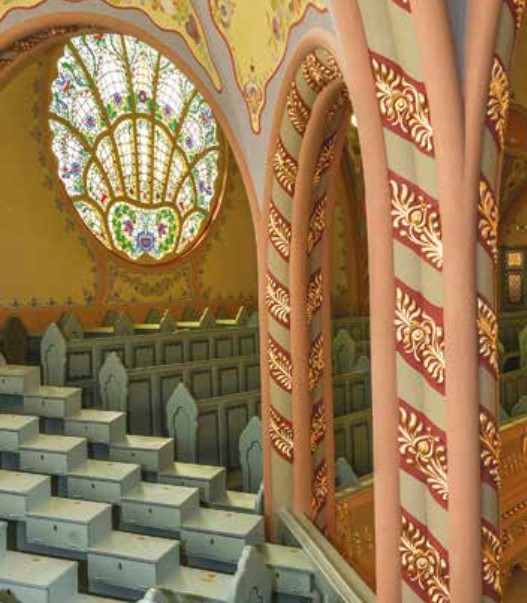

The columns on the galleries turn into vaulted arches on which the convex leaf motifs continue to run uninterrupted. The ground floor space is a bit darker than the rest of it, covered with twilight. Only the stain windows embedded under the galleries illuminates it, and the ornate conical shaped central chandelier with other secondary lighting fittings. The coloristic of each arched stained window is different and unique, but the folk flower motifs repeat. Apart from the functional and aesthetic role of the imposing central chandelier, it has another task - to improve the acoustics of the domed space. The indoor lighting is also provided by a large number of decorative brass lamps. Chandeliers are hanging above the galleries, stylish ceiling or elegant console lamps are glittering the glow of the temple. They almost completely disappeared over time, but have been restored now. The second zone includes the stucco-covered, decorative parapet of the galleries with the bench-rows behind designed for women. The bench-rows slope discreetly disables visual contact with the floor level. In particular, the bench-rows placed in the corners of the galleries provide a unique solution as they are cascading down to the parapets, giving a distinctive visual experience seen from the direction of the Bimah. At this level the LIGHT dominates, which infiltrates from all sides through the huge colorful rosettes and vaulted stain windows, changing constantly, recalling the glow of the Garden of Eden. The foil-shape of the rosettes is reminiscent on carnations. This is where the lead-line with folk motifs fit in. The designers did not intend to create a mystic, sullen space, but tried to engage happiness and enthusiasm into the religious devotion. The basic hue of the ground floor and the galleries wall painting is pale green that symbolizes the spring, renewal of nature and growing life. Green is a mixture of earthly (warm color) and celestial (cold color) principles.

The transition between the gallery zone, (the intermediate world) and the central dome (reflecting the Heavenly Paradise and the Divine Being) was solved with pendentives placed into the corners of the drum of the dome. The pendentives are not structural elements; they are just a visual transition with Matyó folk pattern reliefs, which represent the Tree of Life in flowers. Their color sharply differs from the green environment. On a brick-red background, blue, grayish and pink hues show up. On the oblong surfaces between the pendentives, quotations from the Old Testament can be read in Hebrew and in Hungarian: „Love the Eternity, your God”, and „Love your Fellow as Yourself ”. These ancient messages, such as the whole architecture of the synagogue, color scheme, and iconography recall of the essence of life, proclaim Love.

From that point, the central dome composed of eight segments rises up. It is made graceful by two rows of stained glass windos, despite the light comes in filtered and dimmed through the windows of the outer drum. The color scheme of the dome and its vernacular iconography are consistent and symbolic. The ground-floor conceptualization continues, moving upwards. At the transition zone, still the warm pink tones dominate, and then they gradually melt into light blue, the color of the sky followed by a ledge forming a dividing line on the way to the top of the dome, which turns into dark blue at the very end. The folk flower motifs at the bottom of the dome generally grow out from heart-shaped symbols of universal love, and then run springing around the windows, along the ribbing, right into the radiant Sun on the top of the dome. A gilded radiant Sun with folk floral decoration motifs can be seen also on the vault above the Bimah, symbolizing the Lord’s presence. The highest, most sacred peak of the dome is separated from the lower parts by a mould ring. On this ring rests the peak of the dome - the cone-shaped central stained glass radiant Sun composed of eight-planes with golden yellow and green opal glass inlays on turquoise basis radiating its glow. It is, the source of existence, the only Lord of the known world, originating from eight „All-Seeing Eyes” (not visible from the bottom) placed octagonal on the top of the dome. The All-Seeing Eye is a universal religious symbol; in Freemasonry personalizes the eye of the Great Architect of the Universe. The religious iconography of the synagogue reaches its peak in this central image of the Sole, the Almighty and the All-present.

The most sacred place of the synagogue is the Holy of Holies – the Torah Ark, which generally appeared in the synagogues to replace the original Ark of the Covenant. The Scrolls of the Book of Moses, namely the sacred documents of the Jewish religion are kept inside.

The Ark of the Subotica synagogue besides its Art Nouveau style also carries religious iconography. „The two massive pillars refer to Yakhin and Boaz that stood in front of Solomon’s Temple. The wings that grew out of them were related by architects to cherubs that flanked the Ark of the Covenant, where there is a lulav (palm tree branch), Tablets of the Law and six-pointed star, all in Hungarian folk tradition.” 12 According to the Jewish tradition, the door of the Torah Ark was covered by a parochet (an ornamented fabric symbolizing the curtain that covered the Ark of the Covenant), which is missing today. The two-leafed arched door is formed in an Art Nouveau manner with folk motives, with a Sanctuary Lamp, and a Hebrew inscription above: „Everywhere I see the Lord.” The Torah Ark is painted sky-blue from inside, with stars glittering in gold, imaging the universe. Here you will find the carved Torah holders, following the style of the synagogue.

At the „flashpoint” of the Torah Ark, inside an Art Nouveau shape Star of David a short Hebrew inscription can be read. „It is apparent observing from close, that the YHVH inscription is not original: two Yod letters originally denoted the Lord, and they were over painted with the YHVH letters. In fact, the lettering of the Lord should not be over painted by anything else, but the YHVH inscription denotes the same as the two Yod letters, though less abstractly, so it is thus permissible.”

Above/behind the Torah Ark there is the choir gallery, where the remains of the former organ can be seen. The missing organ pipes were replaced by wooden false-pipes which were restored too, during the last renovation. Originally, in the orthodox synagogues only human voices were allowed to be vocalized, the presence of the organ is already a Neolog custom. The music is a very important element of the religious ritual since, as the spirituality of the organized vibration; it may be the closest phenomenon to the Divine presence, to the supreme principle. According to Dezső Jakab’s memories, the vaulted ceiling over the choir gallery was originally similarly painted as the interior of the Torah Ark, namely the „sky with the stars and planets was visible on it”. The existing pattern was painted only later. On the ceiling, some Hebrew inscriptions, which glorify the music, can be seen: „Praise Him with Stringed Instruments and Pipes” and „Praise Him with Instruments”. The best sound can be heard on the west side gallery.

The construction of the Synagogue in Subotica was completed in only three years, but its restoration lasted more-or-less 40 years. The synagogue was in 1975 and the Ritual Slaughterhouse and the building of the Jewish Religious Community were in 1987 placed under heritage protection as a spatial culture-historical ensemble. In 1990 it received the status of an architectural unity of exceptional significance. Technical restoration of the synagogue began in the second half of the 1970-ies. Since then, restoration works were undergoing more or less continuously on the initiative, by the organization and under the supervision of the Inter-municipal Institute of Monument Protection Subotica (IMIMPS). Due to the uniqueness of the building and the complexity of the task, restoration has been a major challenge for generations of professionals. The continuous lacks of financial resources and of political will were the main reasons for the decades of delay in restoration, which led to „Sisyphus-like conditions”. At that time, to collect money for the most urgent works one had to turn to several sources. The most prominent supporters were the City Council of Subotica, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Religious Affairs from Belgrade, the World Monuments Fund (Jewish Heritage Grant Program) from New York, The Rotschild Foundation (Hanadiv) and different generous individuals.

The year 2014 was a turning point for the troubled fate of the synagogue. The unselfish financial and professional support of the Hungarian state created an opportunity for the entire restoration to be completed by the end of 2017, and the synagogue could regain its original glow and breath-taking beauty, so it could line up among Subotica’s carefully maintained Art Nouveau jewels. The renovation works were supported with more than €2,000,000 from the Hungarian government; guided by the Hungarian National Council; supervised by the Republic Institute for Monument Protection Belgrade and the experts of the IMIMPS; carried out by internationally renowned foreign and domestic restorers, under the leadership of Andrea Fehér civil engineer and executed by the Yumol Consortium from Subotica.

The reconstructed synagogue will be given a new purpose. It will primarily be a tourist destination, but it will also give space for a permanent exhibition and other cultural events, too. For greater religious holidays or commemorations, the members of the Jewish community occasionally may use it as a synagogue. The external and internal renewal of the synagogue was based on the architectural designs of the author of this book and associates due to the fact that construction leading experts had to face a large number of dilemmas during the works. During the comprehensive renovation, they restored the artificial-gilding (Slag Metal) of some decorative elements in the interior of the synagogue. In some places, they have also used real gold plates (Katarina Gold). A special challenge was to decide on the destiny of the overly large number of ground floor benches, and the identification of their original coloristic. Professionals have finally decided to rarefy some rows of benches and so to improve the usability of the interior, but also to restore their original colors. The missing pieces of the colored relief clinker floor tiles were ordered from Morocco, where they were handcrafted peace-by-peace.

The surface color of the exterior plastered parts of the walls was a mystery for a long time too, as the original coloring with the entire plaster was removed and rebuilt in the twenties and seventies of the 20th century. In the memories of Dezső Jakab originating from 1925, he wrote that this color was „green, not yellow and it better harmonized with the red façade bricks, and blue ornaments”.14 The author of this book at the base of the northwestern clock tower found once a plaster residuum with a pinkish hue originating from the brick powder that was added to it as an additive. This, nevertheless, does not prove yet, that the surface of the plaster had never been colored. During the last restoration, the final color of the exterior plaster of the building was agreed with the Jewish Community, to be similar to the color of the desert sand.

By the deadline of December 31, 2017, the 40-year-old reconstruction was over, and the Subotica Synagogue again gained back its original beauty according to its importance.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Chevalier, J., Gheerbrant, A.: Rječnik simbola, Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, Zagreb, 1983.

- Dömötör, Gábor: A szabadkai zsinagóga – 110 év virágzás és pusztulás,Subotica,2012.

- Dömötör, Gábor: The Synagogue in Subotica – Resurrection or Decay (Rehabilitation Possibilities after Carpathian-basin Examples, OmniScriptum BmbH & Co. KG, Saarbrücken, 2015.

- Gazda Anikó, Kubinyi András, Pamer Nóra, Póczy Klára, Vörös Károly: Magyarországi Zsinagógák, dr. Gazda Anikó, Bács-Kiskun Megye, Műszaki Könyvkiadó Budapest, Budapest, 1989.

- Grin, Klaus-Jirgen: Filozofija slobodnog zidarstva – Interkulturalna perspektiva, Biblioteka Duhovna akademija, Ellecta, Beograd, 2008.

- Jakab, Dezső: „A templomról”. Szombat, Szabadka, 1925. december 8.

- Klein, Rudolf: A szabadkai zsinagóga (A zsidó közösség, az építés, a város és kultúrtörténeti jelentőség), Pro reliquiis scribarum Egyesület, Szabadka, 2015.

- Klein, Rudolf: The Synagogue in Subotica, Grafoproduct, Szabadka, 2003.

- Klein, Rudolf: Zsinagógák Magyarországon 1782-1918 – Synagogues in Hungary, Terc Publishers, Budapest, 2011.

- Milkó, Izidor: Hogyan építettük fel a templomot. Szombat, Szabadka, 1925. december 8.

- Várallyay Réka: Az Építészet Mesterei - Komor Marcell, Jakab Dezső, Holnap Kiadó, Budapest, 2006.

DISCLAIMER:

This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of Intermunicipal Institute for Protection of Cultural Monuments Subotica and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union and/or the Managing Authority.